(Article by OpenDemocracy – 27 January 2020, accessible HERE)

Author: Touraj Eghtesad

Last October, I first started to get wind of a strike against Macron’s pension reform. As I am under 30, I didn’t think twice about it. I had yet to discover that this unprecedented call to strike is the clearest example to date of the changing nature of workers’ movements in France. Some call the shift a giletjaune-isation, because it comes from the bottom. A local assembly of trade unions at the RATP (Paris’ transport agency owned by the state) decided to strike on December 5. The strike was announced two months in advance and quickly rallied the railway workers. It has now lasted over 50 days. As I write, the strike is ongoing but has failed to produce concrete results, despite the very new modalities of action which express such profound human creativity and solidarity.

Tensions have been extremely high since December 5, most notably in the first couple of weeks. On a couple of occasions, the Paris metro has been shut down and half of the trains in the country were not functioning. Companies have promoted working from home and university exams were either delayed for a month or even cancelled. The government and the “reformist” unions (centrists like the CFDT and UNSA) called for a truce during the Christmas holidays, which the workers in the major transport companies disobeyed. Both of those unions have since shown support for the reform, leading to a disconnect between their base and their leaders. Many have continued to strike and protest, while others have symbolically ripped up their membership cards and left the CFDT. The remainder of the unions, the Gilets Jaunes and individual citizens have called for a complete withdrawal of the pensions reform.

The pensions reform

The government had originally planned to present the pensions reform in 2019, but had to postpone this because of the Gilets Jaunes uprising. Since then, all that was known was that there would be a point-based system, which Belgium had rejected after mounting a large protest movement of its own. As the right-wing presidential candidate François Fillon famously told business owners in 2017, the only advantage of a point-based system is that it is easy to reduce pensions. Macron’s campaign promise concerning pensions was that he would create a universal pension scheme instead of the many schemes for different professions.

The government insists the reform is about justice between different pension plans. They will be calculated based on one’s entire career, whereas it is currently the 25 best years in the private sector and the last six months of your career in the public sector where wages rise over time which are accounted for. Soon after the movement began in December, the government withdrew plans to change the pension scheme for stewards, police officers and the military to avoid trouble in key sectors.

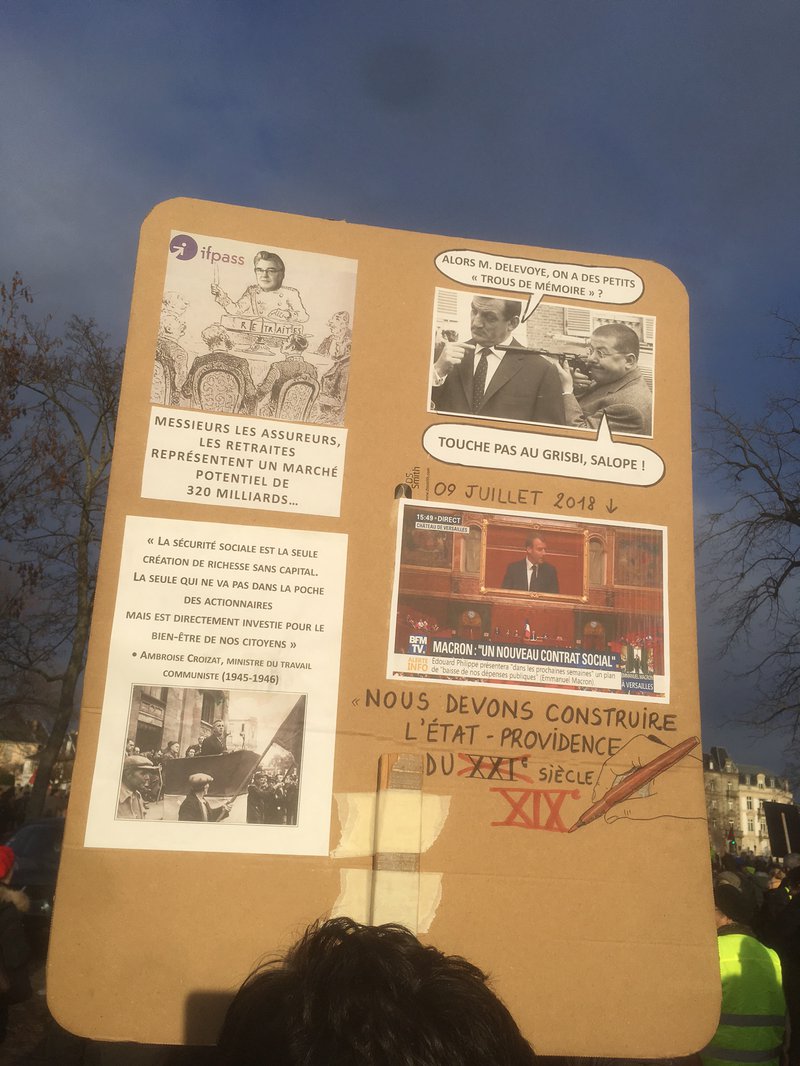

In all the precipitation and mishaps around the law, one thing has become apparent: there is little logic behind such a major law, as was expressed by the Conseil d’Etat (highest administrative court) last week. It will open a market of 320 billion euros for private pension funds, in which people will have to invest to live decently through retirement. One of the major targets of the law’s opponents is Blackrock, the famous American hedge fund, whose president of French operations received the Légion d’honneur, the French equivalent of a knighthood. Jean-Paul Delevoye, the minister in charge of the pensions reform, was pushed to quit once the public became aware of his multiple jobs including conflicts of interest regarding his involvement with insurance companies. So far, this has been the only true concession to the law’s opponents.

Those mobilised are extremely determined for the whole law to be withdrawn. There is too much to lose for many professions: lawyers and chiropractors might no longer make enough to run their own independent offices, public sector workers will lose between 300 and 1000 euros a month, the pension system will be emptied of billions of euros from its wealthiest contributors (above 10, 000 euros per month) and all will have to work longer (up to 64 instead of 62 currently). Pensions have been capped at 14% of the GDP and with rising numbers of retirees, individual pensions will be reduced.

A radical protest

But this protest movement is about so much more than pensions: it is a struggle against neoliberalism and Macron’s authoritarianism, although this is not explicit in terms of demands. Some people feel like a defeat in this struggle will make it difficult to mobilise in the future considering the momentum we currently have. Workers have been mobilised in many different sectors over the past two and a half years and their frustrations are intensifying. Macron has a 25% approval rating and while the wealthy have made record profits since he became president, over a million people have gone below the poverty line.

While the wealthy have made record profits since he became president, over a million people have gone below the poverty line.

It seems like power is hanging by a thread although the government shows no sign of compromise, with local elections approaching in March. The police have been heavily mobilised and have begun in recent days to repress some protests violently. Many unionists have had disciplinary measures taken against them, either by their employer or in court. Macron recently stated that if people think France is a dictatorship, he wished them to go live in a real dictatorship and see what it’s like.

It is refreshing and motivating to feel the solidarity in the air over the past couple of months. Over 1.5 million people protested on December 5 and 17 and there has consistently been 500, 000 people on other days of cheerful protesting. Some energy sector workers have distributed free electricity to those who cannot pay their bill. Tens of thousands of people have contributed to various strike funds, with one of them famously reaching the symbolic 1 million euro mark. In my hometown of Strasbourg, the atmosphere has been very peaceful and positive despite there being few signs of victory. People seem to have faith in the determination of their friends and colleagues.

While some people boast about the strike and protests lasting too long or being useless, over 60% of French people support the strike according to most polls. Strikers have it difficult at times: some people made 0 euros last month. Yet the strike is still strong but many have realised that modalities of action need to change for the movement to continue to build.

Diverse and creative actions

While the mainstream French media reports have been reporting for some time that the strike is dying down or becoming violent, the nature of the movement just seems to be changing.

Several new sectors officially entered the battle in the past two weeks: university lecturers, lawyers, dockers, certain pilots and others. Strikes now focus on specific days and more creative actions are employed to gain visibility. For example, a weekly torch protest has begun on Thursday nights, adding a certain warmth and beauty to marches. The movement is intensifying, with more small-scale sectoral actions and shockupations. These occupations that last a couple of minutes or hours have taken over government buildings, the CFDT office, shopping malls, public squares, etc. This is often interpreted as violence by government officials, who have been overly represented on television the past couple of days, and television editorialists who sacralise private property and often lack nuanced analyses.

The strikers have been a great inspiration and every protest is a moment of reassurance which helps activists give meaning to their action. On strike days, the protest atmosphere has been much livelier than usual. Bridges are being built between experienced activists and newcomers from different sectors. All over France, feminists from the anti-globalization organisation ATTAC have put on their work overalls, performed choreographies and sang parodies of famous pop songs. LGBTQI+ activists have been quite visible in Strasbourg’s protests and have been very vocal with chants emphasising the anti-feminist nature of Macron’s reform. Students have brought plastic gasoline cans to use as drums. Archeologists and certain doctoral students have come dressed up in historical costume. Railway workers have been exploding air cannons and some in public works running electric chainsaws. Scarecrows and signs have been made to parody ministers and their reforms with great humour.

Theatrics and sabotage have also been employed on work days or minor strike days. Firefighters have staged “die-ins’, in front of emblematic places such as courthouses. In Strasbourg, hundreds of them lay down on the floor and let off smoke bombs. Workers at France’s public radio sang the Chorus of the Hebrew Slaves by Verdi to interrupt their director in the midst of a redundancy plan. Lawyers threw their gowns on the floor in front of the Justice Minister during her conference. Doctors then threw their scrubs on the floor and 1000 of them resigned from all administrative tasks in a letter to the Health Minister. Teachers threw backpacks, notebooks and chalk at certain schools and administrative buildings. The Opera of Paris performed a ballet in the street and have been on strike for over 6 weeks. President Macron had to be extracted from a theatre one night after a tip from a journalist on Twitter brought protestors to the door, which reminded observers of the tensions at the height of the Gilets Jaunes movement.

We are witnessing a real convergence of struggles as local groups show solidarity by turning up at each others’ mobilisations.

We are witnessing a real convergence of struggles as local groups show solidarity by turning up at each others’ mobilisations. While all do not go on strike at once, people have been taking turns striking and reinforcements have joined the struggle. As a teacher, I would like to explain the relationship of developments in education to pensions reform.

Education sector

Like other ministers and the president who present this reform not as an austerity measure but a “measure for justice”, the minister of Education Jean-Michel Blanquer has been spreading a lot of rumours. Last week, he suggested that only the 0.1% of teachers who are “radicalised” disagreed with him, in the midst of major opposition to a botched A-Level (Baccalauréat) reform. I wasn’t really surprised to see teachers massively present at the first major protest after that (January 24).

Many teachers who were not at previous protests joined the 5000 or so in Strasbourg. This week, teachers will be dressed in black to celebrate the Baccalauréat’s funeral and to target specific schools. High school teachers have massively begun to strike in the past week and are being replaced by volunteers, jeopardising the right to strike. An 83 year old volunteer fell and was injured last week.

The minister keeps insisting that teachers will not lose out with the pensions reform because their salaries will rise accordingly. Nonetheless, teachers will have to work till they are up to 64 years old, only to have a 1000-1200 euros pension and wages will rise very little. 500 million euros were unlocked for a pay rise in 2021 which will amount to 40 to 90 euros per month, with an emphasis on young professors’ salaries. Constitutional experts suggest that this addition will automatically have to be withdrawn because it is unconstitutional. For teachers who have spent years giving their all for students, these pay rises amount to little more than a communication tactic while pensions fall. Many young teachers feel like they will die before retiring, considering the stress at work (c.f. The sign that takes the famous rhyming expression “underground, workday, sleep” and replaces it with “underground, workday, grave”).

Working conditions are getting tougher each year with larger classes (often 30 students in middle school classes and 40 in high school) due to budget cuts and an inability to recruit new teachers. Widespread attention problems are developing among students and teachers in difficult contexts. They lack support in the face of violence and in addressing learning disorders. Projects that could help to innovate to takle all these issues are simply not being undertaken. Inequality is rising among students and there seems to be an inability to rethink the education system, just like there is an inability to rethink society itself in the age of neoliberalism.

There seems to be an inability to rethink the education system, just like there is an inability to rethink society itself in the age of neoliberalism.

What’s next?

Unions have been declining over the past 25 years, with a reduction of membership and major losses over labour and pensions reforms. The current movement is the largest since 1995, when the government had to withdraw a similar pensions bill. It is the longest strike in French history, surpassing the 6-week general strike in May 1968. Things could still go either way, as the government has failed to convince the public and refuses to negotiate or give in, as would have been the case in previous governments after such a movement. The government is staking its reputation on its ability to go through with this reform and argues that it has negotiated a deal because private discussions have taken place with centrist unions. However, some companies (outside the financial sector) are starting to be exasperated by the disturbances to business and may also put pressure on the government.

What is certain is that society is polarised, although a majority supports the movement.

What is certain is that society is polarised, although a majority supports the movement. Official discourse is starting to criminalise and demonise the movement, which remains peaceful despite police brutality steadily increasing. The government is facing difficulties justifying the reform and has therefore intensified its disinformation campaign. The magazine Le Point’s recent front page stated “How the CGT is ruining France”, while the historic CGT (communist trade union) and its leader Philippe Martinez, now seen as Macron’s number one opponent, is active in environmental, feminist and antiracist struggles. Discussions are now taking place with left-wing political parties, charities, collectives and are perhaps paving the way to a new political project for the country.

The future lies with the strikers at the base, who have shown absolute determination. Many are hopeful that the battle can be won and are willing to sacrifice further pay and time spent with family. In the midst of a cold winter, protestors are still out in very large numbers and the most determined have participated in many actions. The law went through the council of ministers on January 24 and will be discussed in parliament in the coming months although for the first time in history, a law has been filed with many holes yet to be filled in.