RCMF: SLAPPs – Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation

This article was originally published on the Resource Centre on Media Freedom in Europe – 19 December 2019, accessible here.

1. The definition

1.1. Like the pebble thrown in the water

“A large company sues an environmental activist who has exposed a pollution scandal, hoping that the lawsuit will scare away other activists. A powerful business person sues a journalist for defamation after being named in a truthful, hard-hitting corruption story. A real estate developer uses the threat of a lawsuit to silence community opposition to a new building project. And on and on”.

This is what a SLAPP, a Strategic Lawsuit Against Public Participation, is in practice.

According to the international activists’ and lawyers’ task force Protect the Protest, the telltale signs of a SLAPP are that it targets forms of free speech, takes advantage of a power imbalance, threatens to bankrupt the defendant, attempts to remain in court as long as possible, is part of a usually wider public relations offensive designed to bully critics, and follows a pattern of serial bullying, as the plaintiff usually has a history of using SLAPPs or threatening legal action in order to scare critics into silence.

As already stated in 1989, these lawsuits are simply legal tools that aim “to stop citizens from exercising their political rights or to punish them for having done so. SLAPPs send a clear message: that there is a “price” for speaking out politically”.

Originally, the SLAPP phenomenon was a concern only to environmental and community advocates. Now, it targets a wide range of individuals and organisations acting in the public interest, such as civil society advocates, community leaders, journalists, whistleblowers, and citizens in general.

SLAPPs have become a serious threat for media freedom and democratic participation, and require a robust response. “Like the pebble thrown in the water – wrote Penelope Canan in The SLAPP from a Sociological Perspective, 1989 – a single SLAPP can have effects far beyond its initial impact”. These effects on freedom of expression and quality of life, on democracy and quality of journalism, have basically remained unaltered through the years and this dossier will go through them from different perspectives.

1.2. Intimidation and disparity

One of the key elements of a SLAPP is the disparity of power and resources between the plaintiff and the defendant. The plaintiff is aware of the power imbalance and, taking advantage of vague and elastic legal provisions, manages to convert matters of public interest into technical private law disputes, generally with exorbitant claims for damages and allegations designed to intimidate and drain the defendant’s financial resources.

A SLAPP does not need to be successful in court to have its intended effect. In fact, plaintiffs generally know from the beginning that their allegations are groundless or exaggerated, but even if the judge recognises the meritlessness of the lawsuit and dismisses it, the case may stay in court for years, and it can impose high costs and reputational damage on the defendant.

Such lawsuits turn the justice system into a weapon, and have a serious chilling effect on free speech and right to information, as many choose to give up their civil rights if they are not in the position to face the costs of litigation.

1.3. Preventive warnings and the price of silence

To put activists and journalists under pressure, SLAPPs can be used to explicitly blackmail the victims and buy their silence.

Defendants face different kinds of pressure. On the one hand, they are intimidated by the high costs of litigation, and tend to apply self-censorship in order to avoid expenses; on the other hand, in some cases they are even explicitly asked to give up their free speech rights in exchange for the lifting of the lawsuit.

In this case, it is not necessary that a lawsuit is filed: it is enough that a lawsuit is “announced”, as happens for example in Germany, where media’s legal departments see an increase of lawyer’s attempts to prevent journalists from reporting. That was found out by the recent study If you write that, I will sue you! Preventive strategies of lawyers against media , published by the German Otto Brenner Foundation in cooperation with the “Gesellschaft für Freiheitsrechte”. According to its findings, legal departments receive an average of three preventive warnings per month.

1.4. A loss of money, time, credibility: how it works

The tactics of a SLAPP are quite easy to detect: from the plaintiff’s perspective, the longer, the better. As described in the Guide co-edited by Greenpeace, the definition of a SLAPP can start describing how it works.

In the words used by the team of experts, lawyers, and activists in the publication, “a lawsuit can drag on for years, even if it is eventually dismissed. During the litigation, SLAPP bullies will often demand access to your emails, your computer files, and other details of your personal life. A SLAPP can force you to pay thousands of dollars in legal fees, while you have to worry endlessly about going bankrupt if the other side wins. People who were previously supportive of your work might begin to question your credibility. You might waste years of time defending yourself from the lawsuit, rather than working on the issues that you care about. In the end, you, like many others, might agree to end your campaign”.

A silence worth 400 million dollars

The price of silence for the activists protesting against Site C Dam in Northeastern British Columbia amounted to more than 400 million Canadian dollars. “If you sign this commitment to be silent in the future, our lawsuit can be settled”: this is what BC Hydro , the Crown corporation, owned by the government and people of British Columbia, told Ken Boon, a farmer who was protesting against the building of Site C dam in Northeast BC. In 2016, he and other five Peace Valley residents were sued for 420 million dollars in a 13-page lawsuit that accused them of “conspiracy, intimidation, trespass, creating a public and a private nuisance, and intentional interference with economic relations by unlawful means”. They had occupied a piece of land for 63 days to avoid logging of a historical site. And then, they were asked to “stop protesting” for ever. Their silence was priced 420 million Canadian dollars.

2. The International Organisations’ approaches

The problem of SLAPPs varies widely from country to country , depending on legal frameworks that can facilitate the proliferation of this phenomenon, for instance, on the amount of legal costs, on laws targeting freedom of speech, on the absence of safeguards or deterring tools.

However, recently there has been increased attention by international organisations on this issue that can be important in providing viable solutions.

2.1. The United Nations: protection for the people

On several occasions, the United Nations mechanisms and special procedures have highlighted the issue stressing the States’ obligations to facilitate the exercise of the rights of freedom of expression, peaceful assembly, and association.

In particular, States should “ensure due process and protect people from civil actions that lack merit”, and “should introduce for assembly organizers and participants protections from civil lawsuits brought frivolously, or with the purpose of chilling public participation”.

According to the UN’s advice, States should also enact anti-SLAPP legislation, allowing early dismissal (with an award of costs) of such suits and the use of measures to sanction abuse.

2.2. The Council of Europe: decriminalisation

The online Platform to promote the protection of journalism and safety of journalists managed by the Council of Europe (that “aims to improve the protection of journalists, better address threats and violence against media professionals and foster early warning mechanisms and response capacity within the Council of Europe”) lists different kinds of threats to media freedom and to reporters, without a strict distinction between direct and indirect threats. SLAPPs – even though never mentioned there with this acronym, but occurring for example under lawsuits or threatened lawsuits for defamation – are included in the group of acts that have a “chilling effect” on media freedom .

On the one hand, the Council of Europe , “aware of the potential chilling effect of overprotective defamation laws on freedom of expression and public debate”, promotes “decriminalisation of defamation”. According to the CoE, journalists should be neither imprisoned nor threatened with a prison sentence when they are accused of violating other people’s right to reputation and their violations should not be crimes, but civil offences. On the other hand, a strong chilling effect can be obtained even if defamation is decriminalised.

That is why the Council of Europe, besides promoting decriminalisation, “provides guidance to its member states to ensure proportionality of defamation laws and their application with regard to human rights”.

The chilling effects listed by the Council of Europe in its series Freedom of the press and the protection of one’s reputation include the “unreasonably high damages award in libel action: lack of adequate and effective safeguards in legislation and practice” Libel lawsuits with a very high damages award do have a chilling effect on freedom of expression, as stated by the European Court of Human Rights.

2.3. The European Court of Human Rights: too high a price

There are several judgments of the European Court of Human Rights concerning the conflict and the balance between media freedom and the protection of one’s reputation, and one in particular is mentioned by the CoE’s Platform as a forerunner. According to international observers, it is one of the most notorious SLAPPs in European history.

In June 2017, the Court had to judge on a case of a damages award in a libel action where the publisher of the Irish daily newspaper, the Herald, had been condemned to pay over one million Euros in a libel case. The newspaper had published a series of articles about a public relations consultant, reporting on rumours of an intimate relationship with a Government minister. Sued for defamation, the newspaper was condemned to pay 1,250,000 Euros. The publisher claimed that the award had been excessive and had violated its right to freedom of expression.

The European Court stated that “it is not necessary to rule on whether the impugned damages’ award had, as a matter of fact, a chilling effect on the press. As a matter of principle, unpredictably large damages’ awards in libel cases are considered capable of having such an effect and therefore require the most careful scrutiny (…) and very strong justification”.

Moreover, “effective safeguards” should apply to the litigation process as well as outcome.

2.4. The OSCE: free speech

The OSCE Representative on Freedom of the Media‘s mission is to protect and promote media freedom in all OSCE States, monitoring media developments and violations of free expression and free media; activities in this field are focused on ensuring the safety of journalists and on promoting decriminalisation of defamation, as “journalists should not face criminal charges for their work”.

The OSCE does not directly address SLAPP but in 2019, through the signature of the Twentieth Anniversary Joint Declaration: Challenges To Freedom Of Expression In The Next Decade , it declared that States should promote freedom of expression and safety of journalists providing appropriate legal rules and policy frameworks and “limiting criminal law restrictions on free speech so as not to deter public debate about matters of public interest”.

2.5. The European Union: harmonisation, mission impossible

EU institutions have also expressed concern on this issue. Media freedom is a fundamental right that finds protection at the European level through the European Convention on Human Rights and the European Charter on Fundamental Rights, as a pillar of modern democracy and essential component of open and free debate.

The European Parliament has stressed through several Resolutions the importance, among other things, of “coming up with an EU anti-SLAPP directive (SLAPP = strategic lawsuit against public participation), in order to protect independent media from vexatious lawsuits aimed at silencing or intimidating them”, and “encourages both the Commission and the Member States to present legislative or non-legislative proposals for the protection of journalists in the EU who are regularly subject to lawsuits intended to censor their work or intimidate them, including pan-European anti-SLAPP (Strategic Lawsuit Against Public Participation) rules ”.

In 2018, in a cross-party initiative, several MEPs addressed a letter to the European Commission asking for a European response to the SLAPP problem. However, the debate is still ongoing.

As part of its action to defend journalists and media freedom, the European Commission is currently funding several EU projects. Among them, there are some projects run by the European Centre for Press and Media Freedom (ECPMF ) and its partners that provide practical and legal help to journalists under threat, maintain a mapping platform reporting threats to media freedom, and organise training in digital self-defence for journalists.

3. Defamation, libel, and the media

3.1. One definition, many frameworks

Though SLAPPs can be used to claim different kinds of damages (to property, revenues, business, health…), on the basis of different violations (trespassing, privacy, honour…), the most abused lawsuits all over the world concern damages to reputation, thus touching the activity of journalists and the right to freedom of expression. That is why defamation laws are the most common ground where a SLAPP can thrive.

As a study of the Council of Europe confirms, there are some differences from country to country and a general distinction between oral defamation, written defamation, inaccurate assertion of facts, and untruthful words cannot be made. Each legislative framework has its own distinctions and terms. Libel for example is written, while defamation is spoken, but these distinctions cannot be transferred to legislation, as each system has to quickly adapt to the changes of information technology. Other words commonly used when referring to an international framework are slander, insult, abuse, affronts to honour and dignity, and calumny. All these terms have a specific legislative meaning, when referred to a specific national framework.

3.2. The abuse of a legal tool

As stated in a comparative study commissioned by the OSCE Representative on Freedom of the Media, “criminal defamation laws continue to be applied with some degree of regularity across the OSCE region, including against the media. Particular problem areas remain Southern Europe (especially Greece, Italy, Portugal and Turkey), Central Europe (especially Hungary), Central Asia and Azerbaijan, although occasional convictions of journalists continue to take place in states typically considered strong defenders of media freedom such as Denmark, Germany and Switzerland”.

This application of defamation laws, either criminal or tort laws, has relatively little to do with a possible cause-and-effect relationship between defamation and SLAPPs: though some defamation laws are more easily abused than others, defamation is indeed just a pretext, an excuse, a false ground, used and abused with the only aim to silence criticism and stop journalistic investigations.

In fact, the real issue in this context, where legislation and practice concur in balancing freedom of expression and the right to defend one’s reputation, is not the law itself, but the abuse of the law. And SLAPPs are, indeed, abuses of the law.

3.3. Principles and best practices

Considering that a significant number of strategic lawsuits aimed at silencing criticism are filed on the basis of defamation laws, the attention of international organisations has been focused for years on defamation and its regulation. In the last two decades, Article 19 has developed a charter of common principles as a basis of debate and analysis: the aim is to “set out an appropriate balance between the human right to freedom of expression, and the need to protect individual reputations”. The Principles, first published in 2010 and reviewed in 2017, are based on international law and standards, and only include the relationship between media freedom and the protection of reputation, excluding such areas as privacy, self-esteem, or hate speech.

3.3.1 The situation in Scandinavia

In December 2019, OBCT participated in a fact-finding mission led by ECPMF with the aim of finding and analysing best practices in media freedom.

Considering the lack of any sign or threat of SLAPP both in Denmark and in Sweden, the situation was somehow difficult to explain. In fact, both countries have some elements in common with countries where SLAPPs are commonplace, like for example defamation being a crime, with the most severe forms of defamation being punished with imprisonment, but SLAPPs are simply not an issue, neither in Denmark nor in Sweden.

Asked to give an explanation to this lack of abuse, journalists and lawyers interviewed by the delegation provided two elements which can be regarded as deterring the abuse of lawsuits to intimidate reporters and activists; these features, though they can be considered good practices, seem rather difficult to “export”:

- in both countries, the democratic tradition is still uniting people: despite some trends towards polarisation, freedom of expression and media freedom are considered a backbone of the constitutional system and a cornerstone of social cohesion. On the one hand, case law rules in favour of the journalist in most cases, and judges tend to dismiss lawsuits against journalists in most cases; on the other hand, it is also a matter of reputation – no one would sue a journalist, because it is something to be ashamed of;

- one feature of the tort law, where usually SLAPPs thrive everywhere else in the world, is that compensation grants are really low: beside being inconvenient under an ethical point of view, suing is very expensive compared to what one could get awarded as a damage. Being compensations (if awarded) so low, the potential threat of a chilling effect is completely empty.

Croatia

Hrvoje Zovko, president of the Association of Croatian Journalists (HND) had reported last January of “over 1,000 ongoing trials against Croatian journalists or media outlets”. Zovko is also being sued for slander by his former employer, public television HRT, that fired him in September 2018. “In Croatia, it’s open season on journalists”, he had told OBCT a few days earlier, commenting on the increase in attacks against journalists. Beside him, Croatian public television sued for slander 36 between media outlets and journalists, including its own employees, over the last two years.

Serbia

Lawsuits against journalists “are becoming quite common in Serbia, no matter how fact-checked your investigations are. And often top-officials, like ministers, sue the media ”: like Stevan Dojčinović, director of the KRIK investigative portal, told OBCT’s correspondent Francesco Martino, a media outlet can be “sued four different times for the same story”, and the court can deny the request to merge the lawsuits. “So we are currently spending an enormous amount of time, money, and energies to defend ourselves”.

Numbers

Numbers are not enough to tell a story. This is the case for example of Antonella Napoli’s struggle to get rid of a lawsuit filed over 20 years ago : one single SLAPP can capture your whole life. But numbers can be very impressive, as for Federica Angeli, a journalist who has been living under protection for the last 6 years and is fighting against dozens of lawsuits for defamation. At present, in December 2019, she is celebrating her 111th victory in court against a defamation lawsuit.

4. The Search for Solutions

Talking about solutions, George Pring was already aware in 1989 that a solution had to be found right there where the problem is, that is in court: “The best of these solutions lie with our courts – the very institution designed to protect individual liberties and political rights, yet, ironically, the very institution being manipulated to produce the “chilling effect” of SLAPPs”.

4.1. Anti-SLAPP laws in the USA and in Canada

According to a guide written by Austin Vining and Sarah Matthews for the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press, “anti-SLAPP laws provide defendants a way to quickly dismiss meritless lawsuits filed against them for exercising their First Amendment rights. These laws aim to discourage the filing of SLAPP suits and prevent them from imposing significant litigation costs and chilling protected speech”.

Several states in the USA have adopted or amended their anti-SLAPP laws. As of October 2019, 30 states and the District of Columbia have anti-SLAPP laws; in Canada there is an anti-SLAPP law in British Columbia, Ontario, and Quebec.

Anti-SLAPP protections vary significantly from state to state. For the most part, anti-SLAPP laws are broad enough to cover SLAPP suits aimed at silencing or retaliating against journalists or news outlets for critical reporting.

According to West Coast Environmental Law , a Canadian non-profit group of environmental lawyers and strategists dedicated to safeguarding the environment through law, the anti-SLAPP law of British Columbia in Canada will implement a quicker process for defendants to ask the court to dismiss a lawsuit, and they can do it if this lawsuit interferes with their freedom of expression. Like other anti-SLAPP statutes, the law would also allow the court to award additional punitive costs against the plaintiff.

4.2. Looking for European solutions

EU Member States are free to introduce substantive defamation laws and to apply different standards of protection of free speech.

However, the lack of harmonisation at European level allows the proliferation of abuses through the application of private international law (PIL), a body of law dealing with disputes between private persons living in different jurisdictions. In particular, Brussels I Regulation (that governs the choice of jurisdiction in civil and commercial matters) and Rome II Regulation (that governs the law applicable to non-contractual obligations) are involved.

An emblematic case is the one involving Daphne Caruana Galizia and Pilatus Bank, that, despite the overwhelming connecting factors to Malta, brought legal action for defamation in the United Kingdom and the United States. This was possible as the Brussels I Regulation allows the plaintiff in libel cases to choose between the forum of the defendant’s domicile and the forum of the place in which damages are alleged to have been incurred.

Furthermore, as defamation is explicitly excluded from the scope of the Rome II Regulation, the applicable law will be the one of the country in which the damage occurs (Art. 4). In practice, these special rules in defamation cases allow the plaintiff to choose the forum and the law of a country where there are lower standards of protection of press freedom, entailing a possible violation of the defendant’s right to a fair trial.

The susceptibility of defamation cases to forum shopping is sufficient to limit press freedom, as defending a lawsuit in a foreign jurisdiction implies higher costs of proceedings and psychological distress caused by the lack of familiarity with foreign law.

In February 2018, six members of the European Parliament wrote a letter to the European Commission to swiftly initiate legislation to protect investigative journalism in Europe. The cross-party MEPs said that SLAPPs warrant a EU response, and urged the Commission to take action.

In June 2018, Vice President Timmermans replied to the MEPs arguing that the EU lacks competence to harmonise substantive defamation law. However, a forthcoming study by Dr Justin Borg-Barthet affirms that the EU does have competence to intervene on this issue, as the legal basis of the Directive on whistleblower protection may apply also to an anti-SLAPP Directive. In fact, “if it can be argued that whistleblower protection has a direct effect on the functioning of the internal market, as the Commission does in its reliance on Art. 114 TFEU, it must follow that this is also so for defamation”.

Furthermore, the study suggests amending existing legislation and introducing new instruments. In particular, the rules on jurisdiction in the Brussels I Regulation recast should be modified and should follow the courts of the defendant’s domicile, while the Rome II Regulation should be amended in order to harmonise rules on choice of law in defamation, make the applicable law more predictable, and limit forum shopping.

Expert Talk on Anti-SLAPP Solutions

The legal advice by Dr. Justin Borg-Barthet was presented during the expert talk organised by ECPMF and other partners and hosted by the European Parliament, on anti-SLAPP solutions on November 12, 2019 when OBCT presented a focus on strategic lawsuits in Italy.

Moreover, further studies on national procedural and substantive laws in defamation cases should be carried out with a view to adopting a directive that will harmonise minimum safeguards for freedom of expression.

Therefore, at EU level the debate is still ongoing and is focused around a package of short and long-term solutions. In fact, as an agreement among Member States on a legislative proposal has not been reached yet, nevertheless there are other measures that can be adopted to contrast the SLAPP phenomenon.

5. Italy: lawsuits like weapons

The term SLAPP has not yet been adopted in Italy, where strategic lawsuits are called querele pretestuose, cause bavaglio, liti temerarie, stressing their specious, gagging, reckless, and meritless nature. The problem, though, is a daily emergency for journalists.

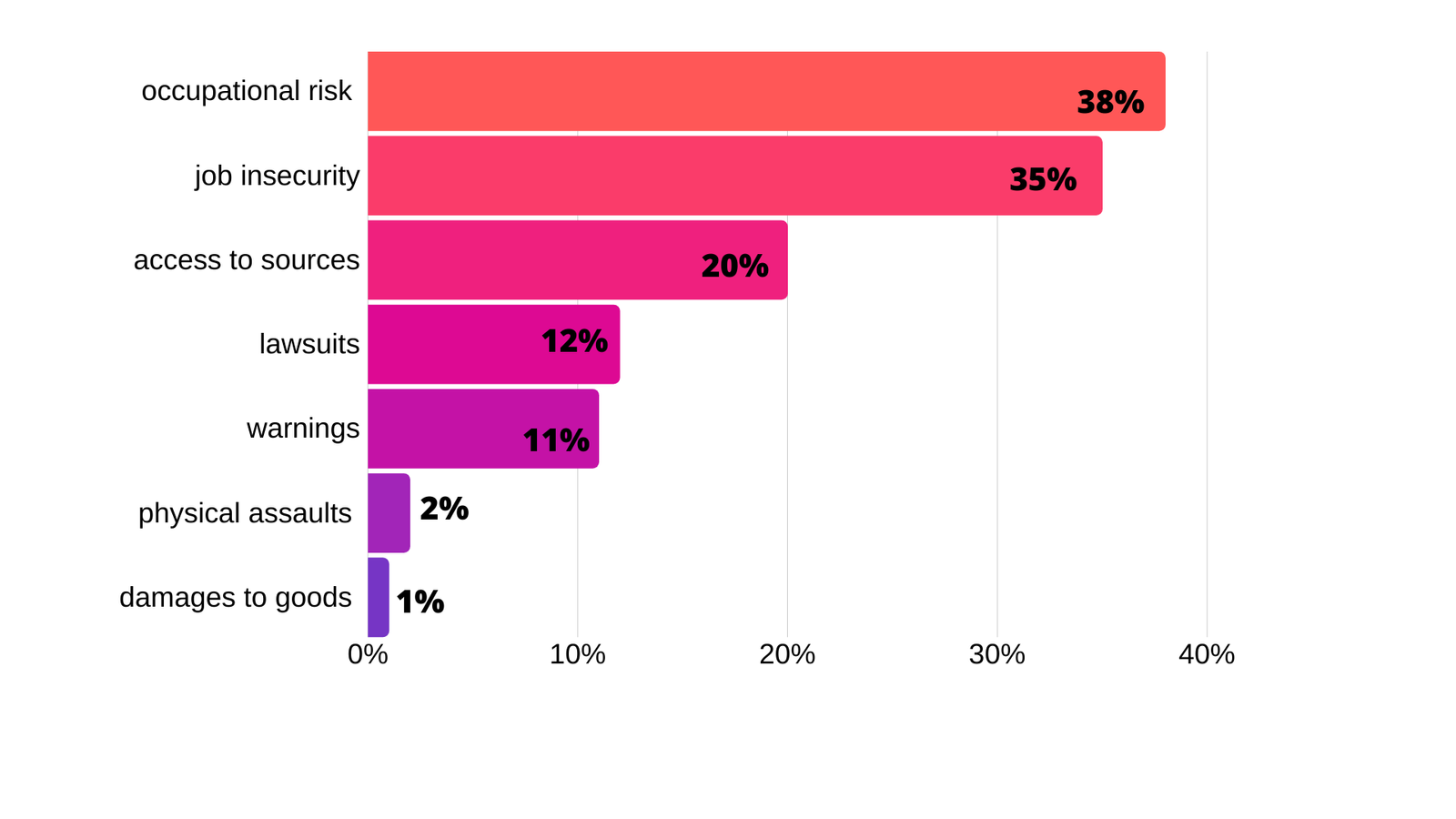

The Italian media environment is gradually deteriorating due to a series of issues that are tightly intertwined. The economic crisis, legislation, and political developments have generated a hostile climate towards the press.

Reporters Sans Frontières ranked Italy 43rd in the 2019, as the level of violence and threats against reporters is alarming and keeps growing. Around twenty Italian journalists are under police protection because of serious threats or murder attempts by the mafia or extremist groups.

Italy also registered the sharpest increase in the number of media freedom alerts in 2018, according to a report by the Platform for the protection of journalism and the safety of journalists managed by the Council of Europe.

Among all problems journalists face on the job, the Italian Communications Regulatory Authority has identified the abuse of lawsuits as the main tool to sabotage freedom of the press.

The so-called querele temerarie, frivolous and meritless defamation lawsuits, are recognised as a “democratic emergency” by journalists’ organisations. As stated by Carlo Verna, President of the Italian Chamber of Journalists, they are an objective restraint to the right to inform and to be informed.

5.1. The legislative framework

As the protection of the reputation of individuals may clash with freedom of expression, it is necessary to constantly balance opposite instances.

The criteria to do so are set out in a landmark judgement of the Court of Cassation (1984). In particular, it establishes that the exercise of the right to news reporting is protected if there is:

- a social utility or social relevance of the information;

- the truthfulness of the information (which may be presumed if the journalist has seriously verified their sources);

- restraint (“continenza”), referring to the civilised form of expression, which must not “violate the minimum dignity to which any human being is entitled”.

Defamation is still a criminal offence that is punished by the Criminal Code and the Press Law. Journalists may face imprisonment up to six years and a fine (up to 50,000 Euros), even though the European Court of Human Rights has repeatedly warned Italy of the potential chilling effect caused by the mere existence of prison sentences for defamation, which constitutes a disproportionate interference with the right to freedom of expression (e.g., in Belpietro v. Italy and Ricci v. Italy).

Furthermore, according to the Press Law, in case of defamation the editors/deputy editor and publisher or the printer (for non-periodical press) can be liable in civil and criminal terms for the failure to conduct supervision of the content of the publication.

To sum up, a vexatious lawsuit is a perfectly legal action that can be undertaken both before civil and criminal courts: it can be filed as criminal proceeding for defamation or as a civil claim for compensation for damages.

5.1.1. Civil claims vs. criminal lawsuits

The Italian Civil Procedure Code entails several procedural advantages that make civil lawsuits even more threatening than criminal ones. In fact, in civil procedure:

- there is no preliminary scrutiny by the judicial authority (and that means longer and more expensive proceedings, while criminal proceedings are most times dismissed even before the trial);

- there is no limit to damage compensation (while in criminal procedure it is around 50,000 Euros – but also in this case it has been considered excessive and disproportionate);

- there is a much longer limitation period for filing an action (5 years against only 90 days in criminal procedure). However, it should also be considered that the crime is time-barred in 6 years, and according to Art. 2947 par. 3 Civil Code, the same prescription period applies for the civil action.

Therefore, the legislator is working on the Civil Procedure Code to introduce more effective legal instruments, as the existing ones – such as punitive damages and mandatory mediation – are not enough.

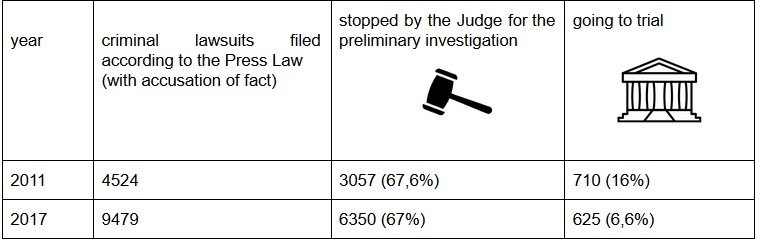

5.1.2. A difficult approach with numbers

Even though SLAPPs have been defined as a “democratic emergency”, it is difficult to quantify the phenomenon.

The main reason lies in the fact that data of civil claims and criminal lawsuits are recorded differently.

For the criminal system, the Italian National Institute of Statistics (ISTAT) database registers lawsuits on the basis of the criminal offence. Conversely, in the civil sphere, lawsuits are recorded according to the civil action: therefore, an in-depth analysis of every single civil file for damages compensation would be necessary, as it is impossible to understand which ones are directly or indirectly linked to defamation and journalism.

Furthermore, statistics do not consider the extensive number of out-of-court settlement of disputes and self-censorships acts.

However, it is worth mentioning that around 70% of criminal cases are dismissed even before the trial thanks to the preliminary scrutiny by the judicial authority (Judge for the preliminary investigation, GIP).

Taking into consideration the extensive out-of-court settlement of disputes, the chilling effect causing self-censorship cases and the lack of provisions that could effectively discourage plaintiffs from starting SLAPPs, it is easy to suppose that this is an even wider and more serious problem.

5.1.3. The Italian paradox

Looking at the international landscape, defamation is a crime in most countries, for instance in 75% of OSCE participating States. Nevertheless, many international media freedom and human rights organisations advocate for “the full decriminalization of defamation and the fair consideration of such cases in dispute-resolution bodies or civil courts”.

But the decriminalisation of defamation and the abolishment of detention penalties for defamation are two different requests, even if they are often mixed and confused. In fact, if defamation is decriminalised, the Italian system will no longer provide the guarantee of a judge’s filter and all damage claims will last for years as it happens nowadays. So far, legislation amendments proposed in Italy do not include decriminalisation.

It is a different matter to ask for the abolishment of prison as a punishment: in this case, defamation would remain a crime (and the system would provide the guarantee of a judge’s filter), but would be punished with a financial penalty instead of imprisonment.

Another concerning Italian feature, probably a paradox according to international standards, is the recurring abuse of hate speech and defamation made through media outlets captured by political parties and/or politicians: too often, media are used as a so-called mud-slinging machine to delegitimise political opponents. That is why, although aware of the importance of the balance between freedom of expression and the protection of one’s reputation, many observers – like Alessandro Galimberti, President of the Regional Chamber of Journalists in Milan, or Antonella Napoli, member of Articolo 21 – feel the need to keep defamation a crime, as a brake and deterrent to the abuse of freedom of insult which often leads to incitement to hatred.

5.2. Factors fostering the chilling effect

A high level of job insecurity precludes the financial capability to react to these lawsuits: usually, journalists are precarious or freelance, and most times, when they are targeted by a SLAPP, they are left alone and cannot count on the support of the publisher, especially at the local level.

Moreover, the simple threat of lengthy and costly legal procedures has a strong chilling effect on press freedom, leading to self-censorship and discouraging journalists from doing their job.

In Italy, the chilling effect of these lawsuits is increased by the excessive length of trials (around six years for a first-degree sentence), criticised and condemned many times by the European Court of Human Rights.

Another element that fosters the chilling effect is that it is extremely easy to file a lawsuit, and since there are no limits to damage compensation, fines could be excessively disproportionate.

5.3. The state of the art in the Italian Parliament

Currently, in the Italian Parliament there are 4 draft bills containing measures to deter strategic lawsuits and to amend media laws (concerning changes to: the editor’s responsibility, the right to have a prompt correction of the news item, the creation of a new judging authority, compensation damages, fines instead of prison for the crime of defamation).

The bills differ in many aspects, but they have one thing in common, namely the cancellation of prison as a punishment for defamation.

Concerning anti-SLAPP provisions, all the bills introduce a kind of “aggravated civil responsibility” with a corresponding punitive damage for meritless compensation claims: if the judge decides that the claim was filed in bad faith, the plaintiff can be condemned to pay a compensation. The bills differ in the amount of the sum to be paid by the plaintiff; the Democratic Party’s bill proposes it as a fine, not as a compensation to the defendant. For more details, see our legal analysis.

One of the bills has been prioritised as it contains an element of novelty for the Italian system, and that is the fixed parameter for the judge to decide the amount of the compensation: the higher the claim, the higher the fine. This proportionality principle is regarded as the main deterrent for strategic lawsuits, since they are dangerous for freedom of expression not only because they are meritless, but also because they are disproportionate in their damage claims. No merit and a lot of money: the worst combination for the greatest chilling effect on journalists.

Critical issues raised by some analysts and confirmed by some members of the Italian Government, include the excessive amount of the penalty, the possible violation of equality, the risk of changing rules, and the need to find new, extra-judicial, ways.

On 17th December 2019 an amended version of Di Nicola’s Bill was approved in the Justice Commission: the punitive damage has been lowered to 25% of the claimed damage (instead of the half). This seems to increase the chance of success of a possible anti-SLAPP solution in Italy.

5.4. Self-defence and counter-attack

Considering that strategic lawsuits are seen by journalists as “a democratic emergency” and that legislative attempts to deter them have either been fruitless in their application or have been aborted within Parliament, journalists have developed several “emergency solutions” to defend themselves:

- as explained by Antonella Napoli, a journalist under police protection, the best way to help colleagues under threat or sued by a SLAPP is to provide them with a “media bodyguard” – in order not to let them feel alone, colleagues should re-publish their investigations and follow up on their findings;

- as decided in May 2019 by the National Council of the Chamber of Journalists, there is the commitment to implement any tool to support journalists targeted by SLAPPs;

- in 2011, the union Associazione Stampa Romana opened the helpdesk “Roberto Morrione querele temerarie”, where pro-bono lawyers assist sued journalists, and since 2015 Ossigeno has been offering pro bono legal assistance to journalists and bloggers facing legal charges or suits.