HUNGARY: a “samizdat” movement brings independent news to the people

(Index on censorship) In Hungary’s rural areas, access to news critical of those in power is a rare thing. Now a small group has set out to challenge the information monopoly of the government by distributing an independent weekly

Last year was a bleak one for press freedom in Hungary. A series of transactions saw the purchase of every local newspaper — more than 500 in all — by businessmen close to the government. Papers like Somogyi Hírlap have become reliable trumpets for the government with a biased and centralised editing team in charge of political stories.

Public media has been broadcasting government propaganda for many years and the few remaining independent online media outlets have a limited reach. Many Hungarians living in the provinces have no access at all to news critical of the government and the ruling party, Fidesz.

But the government’s grip on the flow of information is being challenged by a movement resembling the underground “samizdat” publications of the Soviet Union known for skirting government censorship. “While in larger cities we use term ‘samizdat’ ironically, in small communities our readers actually perceive our newspaper as an illegal publication distributed without the consent of those in power,” János László, the leader of the Nyomtass Te Is (Print Yourself) movement, tells Mapping Media Freedom.

“Our first priority is to help people access news that is censored in the newspapers, TV stations and radio stations close to the government,” László, a former newspaper editor says. “There are still a few independent newspapers and online news websites that work honestly, but they have a limited reach. Our goal is to provide people living in the countryside with points of view other than the severely biased and the unscrupulous propaganda.”

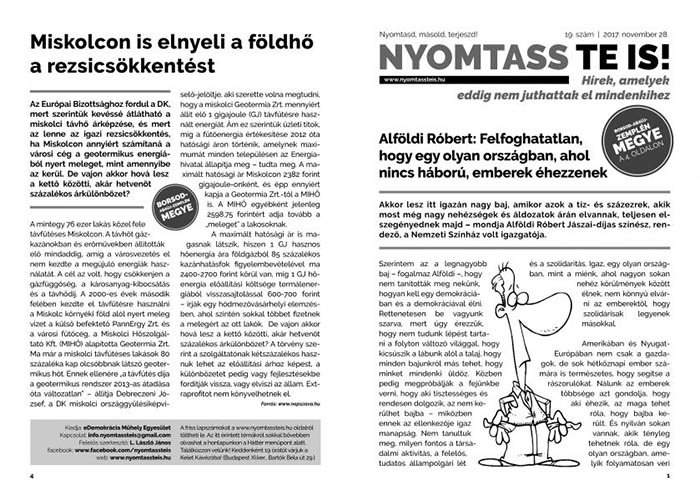

The Nyomtass Te Is editorial team provides a weekly overview of the independent press, selecting stories from outlets such as a 444.hu and merce.hu which aren’t very well known in rural areas, about poverty, corruption, the state of the education and the health system, and rewrite them into short, easily understood articles. Page four of each publication is reserved for local news, where local activists and journalists can suggest pieces. One such article, written by an anonymous author, broke the news of Tibor Balázsi, a former press aide of the mayor of Miskolc, becoming the editor-in-chief position at a local newspaper, Észak-Magyarország.

Activists edit and lay the articles out on A4 pages. These pages are then printed in 50 different locations across the country, put in mailboxes, handed out to people on the street and at bus stations, and left in public places.

The publication is uploaded to the movement’s website, where it is downloaded and printed by the activists who distribute the newspaper. Because the whole process is decentralised and anyone can download and print the newspaper, it is difficult to know just how widely circulated it is, but, according to László, 5,000-10,000 copies are printed weekly. In a city like Miskolc, around 3,500 copies are distributed weekly, while in other places numbers are in the dozens.

“Right now we are present in more than 50 places,” László says. “Our goal is to start from county towns, and from there, to reach the smallest villages. As of January 2018, we have local partners and activists in every county.”

When his crackdown on media freedom is criticised, prime minister Viktor Orbán usually argues that one can publish anything in Hungary, so the press is free, László says, pointing out that press freedom also means a citizen’s right to easily access diverse and comprehensive information regarding public affairs.

The right to be informed is even guaranteed by the Hungarian constitution, but the majority of people living in rural areas still have no access to information other than public media, local newspapers edited by the local government and county newspapers under government control. Every city council publishes a newspaper. Because the most city councils have a Fidesz majority, and the mayor is also from Fidesz, these newspapers are totally biased towards the party.

Unsurprisingly, then, reactions from readers on Nyomtass Te Is’s circumvention efforts are almost always supportive. “Since we started, we have received emails and Facebook messages on an almost daily basis. Most of them are receptive to the idea, and only a small fraction contain anything negative. We receive many ideas on how our publication can be improved and what stories we should cover. We increased the size of our fonts after receiving complaints about readability.”

According to the editor, until now there have been no attempts to their work. “However, in small settlements, our activists are distributing copies of Nyomtass Te Is only at night and in secret.”

The movement is functioning without big donors. Instead, it relies on a lot of voluntary work and small private donations of around of 5-10 thousand forints (€15-30). The money is spent almost exclusively on printing.

As for the future, they are planning to apply for the funding opportunity titled Supporting Objective Media in Hungary by the US. Department of State, which would mean a funding of $700,000 for media operating outside the capital in Hungary to produce fact-based reporting.

Orginal article by ZOLTAN SIPOS on Index on censorship

Featured image via Index on censorship